Virginia’s ranking fell more than any other state in the in the Commonwealth Foundation’s 50 State Labor Report “The Battle for Worker Freedom in the States: Grading State Labor Laws.”

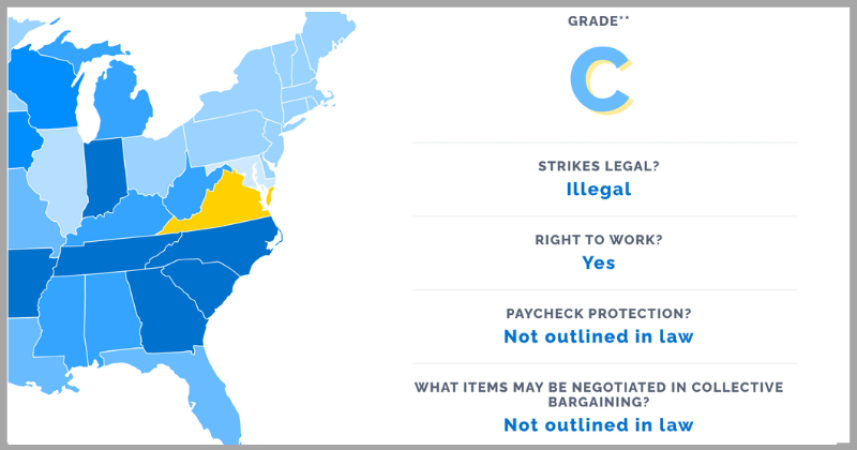

Virginia plunged from an “A+” ranking in 2019 to a dismal “C” this year. This was due to what the report called “[t]he most dramatic government union victory of the post-Janus legal frontier” – Janus being the 2018 Supreme Court case Janus v. AFSCME declaring everything government unions do is political, and public employees have a First Amendment right not to subsidize this political activity. It essentially brought right-to-work provisions to public employees across the country.

As the report noted “Three states experienced major grade changes since our 2019 report. Virginia dropped from “A+” to “C” for instituting collective bargaining, while Arkansas jumped from “C” to “A+” for banning it. Missouri’s comprehensive labor reforms were officially struck down, moving the state back down from “B” to “C.”

The reason for the fall was a law that went into effect in 2021 allowing localities to grant public employees the privilege of collective bargaining — something that had been illegal in Virginia for decades. Because of the new law, Virginia counties, cities, and school boards can enact ordinances giving government unions a monopoly to negotiate contracts for nearly all their public employees.

One of the large problems is that there are no guardrails on the legislation besides saying ordinances must have an unspecified mechanism for how unions can be formed and removed, and requiring local government take a vote if they are petitioned by a majority of public employees working at a specific job.

Besides that, and unlike most other states around the country which do specify what unions can bargain over, the law made Virginia the Wild West for collective bargaining. Anything not specifically prohibited by other provisions of state law was fair game.

Unions in Virginia can now pressure localities to give them more authority and privileges. The Commonwealth Foundation report offers Alexandria as an example. The City of Alexandria originally sought to give unions the ability to bargain but have that privilege limited to wages and benefits.

It quoted City Manager Mark Jinks’ worries about flexibility especially in light of emergencies like the recent pandemic which he said was a “large-scale macrocosmic example of how the City government needs to respond to crises and needs large and small, often immediately” Specifically, Jinks noted “COVID-19 required major shifts in how work was undertaken, immediate safety protocol development and implementation, reassignment of many City employees to new tasks not in their job descriptions, and dramatically changed work environments.”

Collective bargaining contracts in other states precluded flexible and immediate pivots in government services during the Covid emergency, even to the point of holding up online education services at the demand of the teachers unions.

Yet after unions such as the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) put pressure on the Alexandria and its manager, the Ordinance was changed and the report notes “unions succeeded in including issues such as grievance resolution, safety, hours, and other working conditions in the final ordinance.”

The report also pointed to potential cost increases that will “likely put pressure on officials to raise taxes on state residents.”

This is not something that has escaped localities planning to pass bargaining ordinances. As of April of 2021 Fairfax County forecast a need to allocate $1.6 million for increased administrative costs due to bargaining for the county and the school division.

Loudoun County’s proposed FY 2022 budget included over $1 million to pay for extra staffing and overhead.

Estimates from the City of Alexandria were between $500,000 and $1 million per year for administrative costs.

The Commonwealth Foundation report grades states on the legality of public sector bargaining and it scope. It also gives weight to issues like release time (union officials paid with taxpayer funds to do union work), strikes, transparency, the ease with which an employee may leave or opt-out of a union, and right-to-work.

Virginia did have a few positives. The state protects employees with a right-to-work law — meaning a union cannot get a private sector worker fired for not paying them, although this is a right already granted to public employees thanks to the Janus case.

Virginia also has a secret ballot protection act and laws prohibiting strikes. However, provisions that have already been included in local ordinances are troubling signs. These include release time, almost unlimited bargaining, limitations on when public employees can exercise their rights due to arbitrary windows when they can leave and stop paying the union, and other issues.

Overall, the fall in ranking represents a worrying sign for Virginians and public employees across our Commonwealth.

F. Vincent Vernuccio is Visiting Fellow with the Thomas Jefferson Institute for Public Policy and President of the Institute for the American Worker. He may be reached at Vinnie@VernuccioStrategies.com.