Nonprofit hospitals in low-income neighborhoods should be the backbone of the American safety net system for low-income people who lack insurance. Instead, thanks to a federal program called 340B, many nonprofit hospitals have made maximizing revenue their primary goal, not providing charity care. Thanks to a New York Times investigation, Richmond Community Hospital has become the starkest example of a nonprofit hospital that exploits the 340B program while reducing medical services available to the distressed community surrounding the hospital.

The 340B program was created by Congress in 1992 and it was intended to allow about 500 hospitals in low-income areas to purchase drugs at substantial discounts. It was thought that, with these discounts, nonprofit hospitals could provide more free care to the distressed communities where they were located.

However, the law was poorly written, and hospitals soon discovered that they could “arbitrage” these drug discounts into a profit center. How could they do this? In short, buy low and sell high. As the NY Times story explained, Richmond Community can buy a vial of the cancer drug Keytruda at a discounted price of $3,444 yet can bill the local Blue Cross health plan $25,425 for that same vial, for a profit of $22,000 on one patient’s prescription.

The Lown Institute, a nonpartisan think tank calculated the “fair share deficit” of each state – the amount spent on charity and community investment minus the tax breaks received by the hospitals. Virginia ranked 34, with hospitals in the aggregate receiving $292 million more in tax breaks than the amount they spend on charity care.

This no doubt contributed to the growing profits of Virginia’s hospitals, most recently observed in a 2017 Thomas Jefferson Institute study.

These incentives caused Richmond Community to expand into wealthier neighborhoods so they could enroll more patients with good insurance coverage. After all, if Richmond Community gives Keytruda away for free, it will cost them $3,444, but if they prescribe it to a patient with insurance, they would profit by $22,000. The Times story describes how Richmond Community opened a cancer institute in a wealthier neighborhood in order to increase its revenues from the 340B program. “The Bon Secours Cancer Institute at St. Mary’s, for example, administers cancer drugs to patients in an office suite on the tree-lined campus of St. Mary’s Hospital.”

Richmond Community can expand into higher income neighborhoods because these satellite offices immediately become eligible for the 340B discounts that derive from the main hospital’s location in a low-income neighborhood. Congress wrote the law so poorly that they did not preclude satellite offices in wealthy zip codes from sharing the discounts.

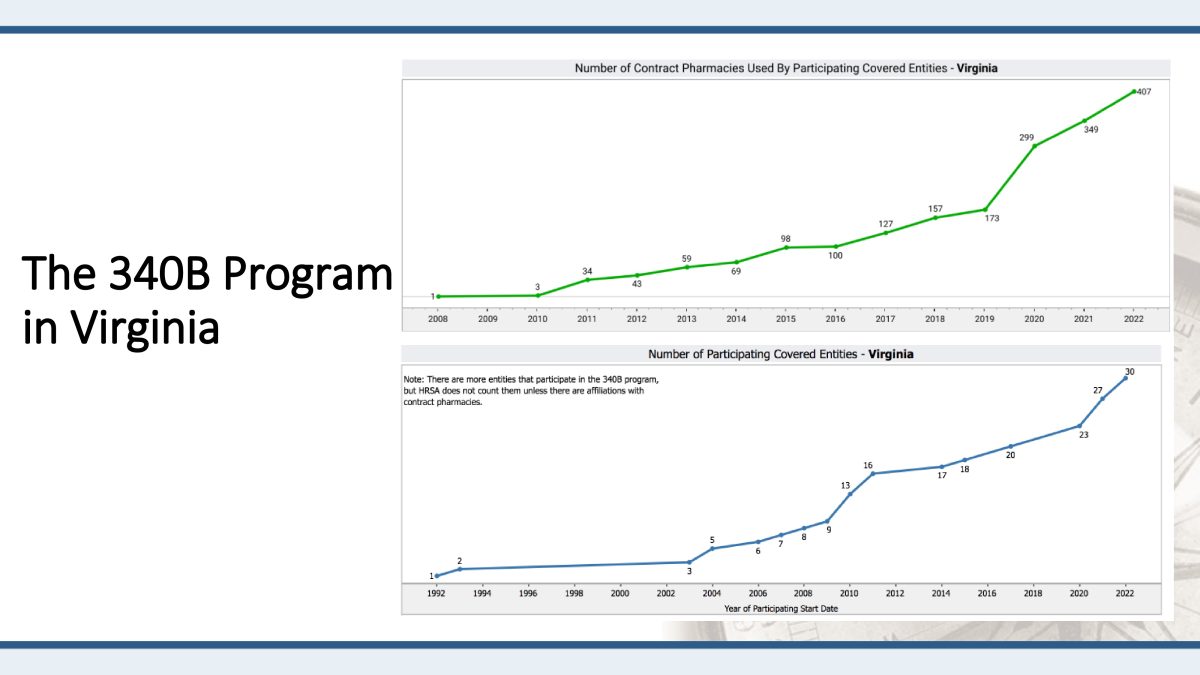

The result has been that the number of contract pharmacies has skyrocketed as has the number of covered entities, far above just the number in low-income areas.

However, probably the worst aspect of the statute creating the 340B program is that it does not require hospitals to spend the 340B revenues on charity care for the local community. So, few policy makers know how much revenue hospitals get from the program and what they spend it on. As the NY Times explains the infirmities in the law: “Hospitals did not have to disclose how much money they made from sales of the discounted drugs. And they were not required to use the revenues to help the underserved patients who qualified them for the program in the first place.”

Therefore, the Congress and state governments can undertake a simple reform to help with this situation: disclosure. First, policy makers should develop a uniform definition of charity care.

For example, an unpaid bill from the wealthy patient does not count as charity care. Then, they should require that hospitals disclose how much revenue they secure from 340B and how much actual charity care they provide.

With this simple reform, policy makers and the public at large can know if nonprofit hospitals are living up to their mission.

William S. Smith, PhD, is Senior Fellow and Director of the Life Sciences Initiative at Pioneer Institute in Boston. He may be reached at wsmith@pioneerinstitute.org.