Reason Foundation recently released its 25th Annual Highway Report, a yearly evaluation of the conditions and cost-effectiveness of state highway systems. The report uses data reported by states to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) as a condition of receiving their federal highway funding. The FHWA data are supplemented with bridge data from Better Bridges magazine and congestion data from INRIX. The report compares each state’s highway spending against its highway system’s performance to provide policymakers and taxpayers with an assessment of value-for-money spent.

Continuing a national trend over the last 20 years, the overall state highway system performance improved slightly. Most of the trouble spots are concentrated in the lowest-scoring 10 states, which have a disproportionate share of the highway problems and reduce the overall system performance.

This year’s Annual Highway Report examines 13 categories; four categories measure state spending and nine measure performance. Across the country overall, seven of the nine performance categories improved: Rural Interstate Pavement Condition, Rural Arterial Pavement Condition, Urban Arterial Pavement Condition, Structurally Deficient Bridges, Fatality Rate, Rural Fatality Rate, and Urban Fatality Rate. The two performance categories where conditions worsened: Urban Interstate Pavement Condition and Urbanized Area Congestion. Unfortunately, this increase in system performance comes at a substantial cost. Capital and Bridge Disbursements increased by 8 percent, Maintenance Disbursements by 14 percent, Administrative Disbursements by 8 percent, with Total Disbursements up by 9 percent.

For this newsletter’s audience, it’s particularly important to note that the report is a measurement of the roadways that each state owns and operates, not a ranking of the state departments of transportation. We also made one methodological change in this year’s report worth noting. Instead of calculating disbursement rankings using lane-miles, we used an average of centerline-miles, lane-miles, and vehicle-miles traveled per lane-mile. Centerline-miles are the length of the highway system (a five-mile road equals five centerline-miles). Lane-miles are the length of the highway system multiplied by the number of lanes on a highway (a five-mile road with two lanes equals 10 lane-miles while a five-mile road with six lanes equals 30 lane-miles). Vehicle-miles traveled per lane-mile are the total amount of miles traveled on the state highway system divided by the lane-miles in the state (100,000 vehicle-miles traveled per year divided by 200 lane-miles of roadway equals 500 vehicle-miles traveled per lane). We made this change in an ongoing effort to be fairer to all the states. While a centerline-miles ranking may favor rural, less-populated states, a vehicle-miles traveled per lane-mile ranking may favor urban, more-populated states. Therefore, we believe a composite measure can help provide a more accurate, richer dataset.

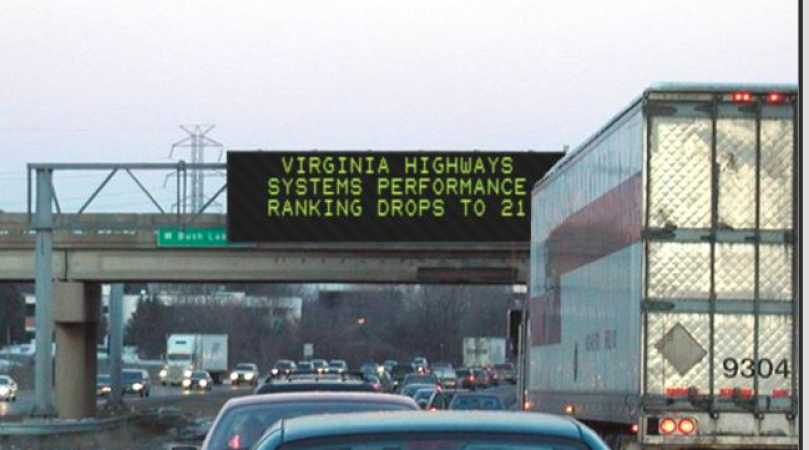

Generally speaking, this change had a modest effect on the report’s overall rankings. Eleven states saw a movement of 10 positions or more in the rankings. Arkansas, Mississippi, Wisconsin, South Carolina, and Iowa improved dramatically in the overall rankings—by 23, 17, 16, 14, and 11 positions, respectively. In contrast, Wyoming, Maine, Virginia, West Virginia, Oregon, and Vermont saw their rankings worsen by 25, 21, 19, 17, 16, and 11 positions, respectively.

For the past three editions of the Annual Highway Report, North Dakota has been the top-performing state in the study’s overall performance and cost-effectiveness rankings. But the state’s overall ranking is not a function of placing number one in any particular category. Rather, North Dakota ranks first overall because it scores in the top 30 in nearly all—12 of the report’s 13—categories. And it ranks in the bottom 10 states in only one category—Structurally Deficient Bridges. Its next-worst rankings are 28th in Urban Arterial Pavement Condition and in Rural Fatality Rate. Solid performance in nearly every category is what drives North Dakota’s overall ranking.

A far more-populous state, Missouri, ranks second overall in the report. Missouri also benefits from consistency across the board. Missouri does not rank in the bottom 10 in any of the 13 categories. Its worst ranking is 33rd in Structurally Deficient Bridges. Missouri shows that a more highly populated state (18th largest), with a large state highway system (7th largest by mileage), can rank highly in the report’s overall rankings and can serve as a model for other large states looking at lower rankings.

The worst-performing state is once again New Jersey, which ranks well in only two categories. The state ranks 3rd in Overall Fatality Rate and 4th in Rural Fatality Rate. But New Jersey is last in the overall rankings because of its poor performance in a large number of categories. The state has the highest Total Disbursements, Capital/Bridge Disbursements per Mile, and Maintenance Disbursements per Mile. It also ranks in the bottom five in Administrative Disbursements Per Mile and Rural Arterial Pavement Condition. In short, New Jersey spends far more money on its roads than the average state for a small state highway system that performs worse than average.

We frequently hear that it is unrealistic for New Jersey to have the same performance as North Dakota. But states such as New Jersey could focus on improving pavement conditions and reducing traffic congestion. It ranks in the bottom 10 in three different pavement condition categories, for example. Improving pavement conditions would help its rankings. Or, New Jersey could choose to focus on efficiency and reducing its spending somewhat, which would also significantly help its rankings. Reducing the state’s per-mile expenditures to levels that are comparable with states with similar geographic characteristics, such as Maryland, would help.

While it may be unrealistic for the worst-performing states to become top-ranked states quickly, they can make tangible progress on road conditions, deficient bridges, traffic congestion, and improve in ways that take them closer to average performance- and spending-levels for similar states.

States that rank poorly can also learn from other nearby states. Each state has strengths and weaknesses. For example, Georgia has long been an expert at maintaining high-quality urban Interstate pavement at an affordable cost. In contrast, Arkansas struggles at maintaining high-quality pavement. Thus, Arkansas officials might consider looking at the rankings and speaking with Georgia’s transportation officials about how they maintain their pavement quality. Transportation departments can use the report to see which states are succeeding in various categories and take the best practices from a variety of places.