Virginia’s state budget grew 90% in the past decade, far faster than in previous decades. After adjusting for inflation and population changes, spending still jumped 4% each year, a high rate of compound real growth. At the same time, the state continues to see explosive growth in its revenue, pointing to cash surpluses continuing for some time.

These facts emerged from two presentations to the Virginia General Assembly this week. The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) issued its annual report on state spending growth on Monday. That same day, Secretary of Finance Stephen Cummings reported on the revenue results from July through September, the first quarter of Fiscal Year 2024.

In just those three months, revenue exceeded the revenue estimates by more than $412 million. Other months, with larger pots of projected revenue, are still ahead. Should this revenue trend hold, surpluses similar to the historic surpluses of Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023 could result next June.

During the elections two years ago, Virginia’s flush financial condition was inspiring debates about tax reductions and tax reform. Some, but not all, of the proposals went on to pass. But with General Assembly elections just over two weeks away, few candidates in either party are promising more tax reform or reduction efforts in the next session.

Secretary Cummings openly expressed the cautious attitude of Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin’s administration. Youngkin and Cummings last week heard their own advisory panel of economists report they expected no recession or at worst a mild one as the battle with inflation continues, but they apparently disagree.

Stubborn inflation is one reason Cummings cited, but they also are worried about the impact of the ongoing war in Ukraine, the new conflict between Israel and the terrorist army of Hamas, and the wave of strikes sweeping the U.S.

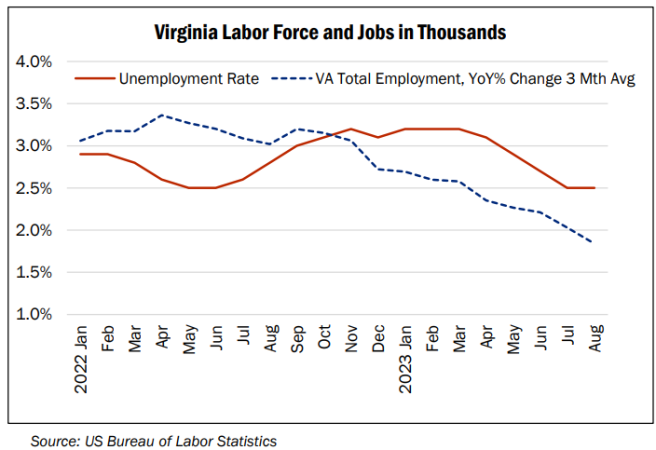

As has been the case for a while now, the strong revenue growth is mostly generated from the corporate income tax and that portion of the personal income tax paid by individuals through quarterly installments. Those revenues are usually from people earning income from businesses or investments. The portion of the income tax from payroll withholding is also growing, another good sign, but it is only about 1.4% ahead of projections.

Sales and use tax revenues for the quarter also showed only modest growth, but exceeded the official forecast that they would sink by almost 7%. That has not happened so far. For those who like details, here is the full set of financial summaries presented.

Cummings made the same presentation to the House and Senate committees that write the budget and tax rules. He received only one or two minor questions. The “bumps on a log” response from legislators, again, is very telling during this hot election season. The Senate Finance and Appropriations Committee in particular is dominated by senior legislators who are not running for new terms.

The JLARC report on spending for Fiscal Year 2023, and for the decade of 2014-2023, included the claim that “average growth rates” it reported were “slightly higher than in prior decades.” Slightly? A look back ten years to the 2013 report points to obvious acceleration. For example, the General Fund side of the budget grew 38% in the decade ending July 2013, and then another 74% in the decade ending July 2023.

In dollars, spending grew from just over $17 billion in 2013 to just under $30 billion in 2023. But it doesn’t seem to be causing anybody any heartburn. Neither does the $81.1 billion total for last year.

Virginia splits things between the General Fund (GF), mainly the tax sources, and what is called the Non-General Fund (NGF), mainly federal funds, motor fuel and vehicle license fees, college tuition and fees, and state hospital revenues. The NGF side of the budget doubled, a full 100% growth, over the last reporting period. It went from $25.6 to $51.4 billion.

You can see the bump of massive federal funding related to the COVID-19 pandemic in the charts, but that abated substantially before FY 2023, the endpoint for the decade of comparison. Because of those Covid funds disappearing, total spending for FY 2023 actually dropped from the previous year. The COVID dollars were all part of NGF.

The report covers where the spending growth has happened, and as usual, most of the growth in spending was in just a few agencies or programs: the Medicaid health services to the poor (11% per year), state payment to local public schools (6% per year), transportation (9% per year), and the premier universities (University of Virginia, 6% per year and Virginia Tech, 4% per year.) Those reflect total budgets which includes both federal funds and college tuition checks.

If we look instead at just the GF spending, the income and sales tax dollars, the pattern basically holds. The largest increases in this category were in public education assistance (6% per year), the state share of Medicaid (6% per year) and higher education’s general account (6% per year.) Health and education programs have gotten most of the new dollars by far and are usually the main focus of demands for even more.

JLARC actually started with the annual spending growth reports in 2002, and the first report looked at data as far back as 1981 (GF of $2.7 billion) and tracked 20 years of spending growth. The trend of spending growing faster than the state’s population and faster than inflation was already well established.

Can the trend be reversed, or at least can the rate of climb be reduced? Elections are the time when that proposition can and should be put to the voters. Otherwise inertia rules.

Steve Haner is Senior Fellow for State and Local Tax Policy at the Thomas Jefferson Institute for Public Policy. He can be reached at Steve@thomasjeffersoninst.org.